Mikhail Naganov

Desktop Stereo Setup

A couple of months ago we have moved into our new house, and I had to spend some time setting up sound in my new office room. This time I decided to focus on the listening experience while working—that is, while I’m at my standing desk. I’m lucky enough being able to avoid using headphones most of the time. Thus the task was to create a good near-field stereo setup.

In my understanding, a good stereo reproduction means achieving a clean separation between virtual sources, and that feeling of being “enveloped” into the music. I want to perceive a wide soundstage which expands beyond the speakers. And I want to be able to almost feel the breathing of the vocalist.

What’s great about the personal desktop setup is that clearly there is only one listening position, so it’s much easier to optimize the sound field. What’s harder, though is that the speakers are at a very close distance so it’s not easy to make them to “disappear.”

The Equipment

I decided to start with the equipment that I already have and see how far can I progress with it. This is my hardware:

- 4 items of 2-inch wide sound absorbers by GIK Acoustics (freestanding gobos);

- a pair of KRK Rokit 5-inch near field monitors—the old 2nd generation released in 2008; I was doing some measurements of them a while ago;

- one Rythmik F12G 12-inch subwoofer;

- my faithful MOTU UltraLite AVB audio interface;

- a Mac Mini late 2014 model.

I couldn’t use my LXminis on a desktop because they are too tall, so I had to stick with KRKs.

The Philosophy

These days it’s rather easy to take some good DSP room correction product and leave to it all the hard work of tuning the audio system, expecting “magic.” However, I decided to stick with a bit different approach and make sure that the DSP correction is only “a cherry on the top of the cake,” meaning that before I apply it, I have already achieved the best possible result by other means.

I decided to proceed in the following steps:

- make sure the acoustics of the room and the geometry of the setup are done right;

- align the speakers as close as possible by using their built-in controls—both KRK fronts and the subs offer some;

- apply basic DSP treatments with PEQ filters of MOTU AVB;

- finish with a speaker / room FIR filter correction done using Acourate.

This approach has an advantage that on every stage we have as good as possible system, and try to improve it on the next stage. Also, the first 3 stages do not require the system being connected to a computer. I realized that it’s a bonus after my Intel NUC machine which I used for running DSPs has died one day without a warning.

The Space

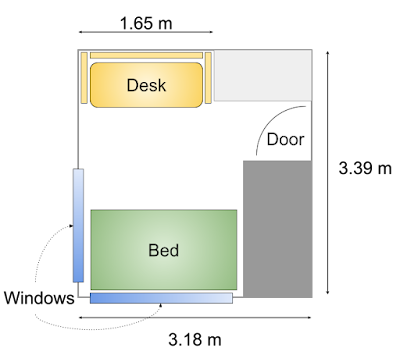

My office room is rather small: approximately 3.39 x 3.18 x [2.5–3.6] meters, and is highly asymmetric—which is actually a problem. Below is its plan:

There are not many options for placing the desk. I decided to stay away from the windows and put my setup into the niche on the opposite end. There I’ve mounted the sound absorbers on the walls surrounding the desk. This is how the setup looks like:

There are still some asymmetries (see the marks on the photo):

- the ceiling is slanted;

- the subwoofer is used instead of a speaker stand on the left;

- there is a wall on the left, but an open space on the right.

The space behind my back (as I’m working at the desk) is completely untreated. More or less, the room space uses the same concept as LEDE design for audio control rooms. However, the amount of acoustic treatment on the front is certainly less than they use in professional environment—it’s a living room, after all.

By the way, placing the subwoofer on the desk was intentional. Following the principle to start with physics, I decided to put it as close as possible to one of the front speakers in order to create a full-range speaker with almost no need to time align them using delays. Although this makes the setup even more assymetrical, the fact that the subwoofer only needs to cover the frequency range below 50 Hz makes it a minor problem.

Physical Alignment

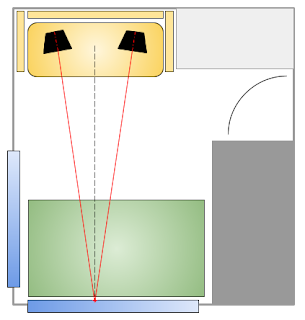

So, placing of the subwoofer was one thing. As a happy coincidence, placing the left monitor on it for creating a full-range speaker have also put the monitor at the correct height relative to my ears. I often heard the advice that the tweeter of a multi-way speaker should be at the ear height, however, I don’t think it’s completely correct. As Bob McCarthy points out in his excellent book, in a system where the high- and low-frequency speakers are time aligned, placing the midpoint between them at the ear level better preserves the alignment in the horizontal plane:

No need to mention that both left and right speakers are set at the same height.

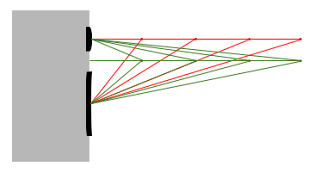

In the horizontal plane, the speakers and my head form the recommended equilateral triangle. Initially I tried “aiming” the speakers at the point immediately behind by back, thus forming the standard 60 degree angle. However, this has created a very narrow soundstage. After some experiments I have arrived to the arrangement with the speakers aimed at the point on the window far behind my back:

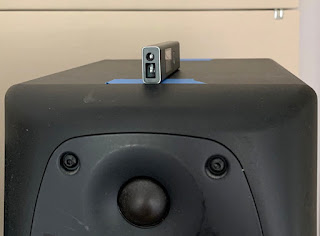

For precise aiming, I used laser distance meters placed on both speakers. They have crossed very close to each other, also confirming that both speakers are aligned vertically as well as horizontally:

The process of physical alignment was finished by placing the measurement microphone equidistant from speakers, according to length measurements. Now the time had come for acoustical alignment by means of electronics.

Basic Acoustic Alignment and Measurements

This step included making sure that the front speakers are aligned as much as possible, and the left speaker is aligned and synchronized with the sub. At first I was only using the speakers’ built-in controls and watching the result in real time using the dual channel (transfer function) measurement in Smaart V8.

The KRK Rokits only offer two knobs: the overall volume and the volume of the high-frequency amplifier driving the tweeter. The controls of the Rythmik’s sub amplifier are more sophisticated, allowing to adjust the bandwidth of the sub, the delay, enable one PEQ filter, and much more.

Besides looking at real-time measurements in Smaart, I’ve also made a traditional low speed log sweep in Acourate which had provided me a bit more insight into the problems that I had with my setup.

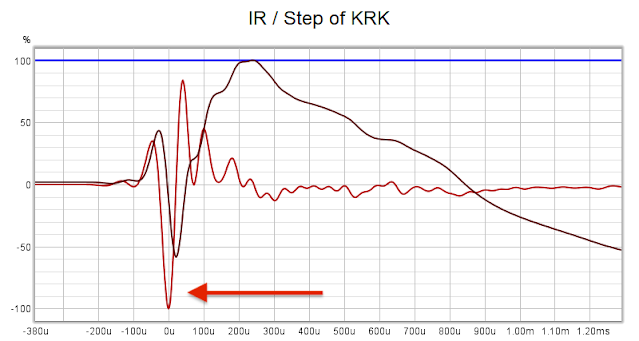

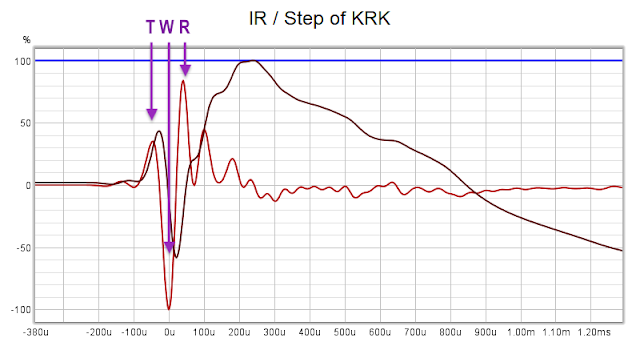

First, by looking at the impulse and the step response of the KRK Rokits, it had become apparent that the woofer’s polarity is inversed:

Not sure why this was done by the speaker’s designers. As a result, since the woofer also runs in an inverted polarity compared to the bass reflex port, their counteraction creates a very steep roll-off at low frequencies below the speaker’s operating range. However, since the output from the woofer dominates in terms of delivered acoustic energy, it was also counteracting the subwoofer. The solution I’ve ended up with was inverting the polarity of both front speakers by using XLR phase inverters. This phase inversion isn’t audible by itself, but it indeed helped to integrate the left speaker with the sub more easily.

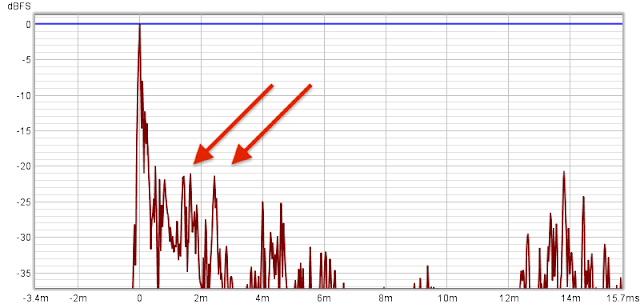

The second finding was that the untreated part of the wall on the left, and the ceiling do create visible spikes on the ETC graph during the first 5 ms, which means they affect the direct sound of the speakers:

I have confirmed where the spikes are coming from by temporarily covering the wall and the ceiling with blankets. But I couldn’t do much for now.

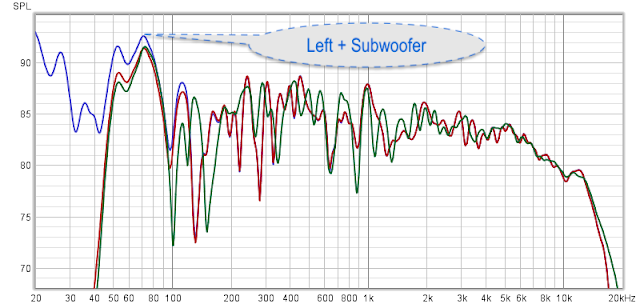

Looking at the amplitude part of the frequency response, I could see that the fronts have a sharp roll-off after 50 Hz, and that adding and aligning the sub allows to cover the missing low-end down to 15 Hz:

We can also see that the direct sound from the tweeters is mostly aligned, but the midrange is spiky both due to reflections and room modes which can go up to quite high frequencies in such a small room.

Correction with PEQs and Setting the Target Curve

After squeezing as much as possible from the built-in controls of the speakers and fixing the polarity problem, I did some corrections to the most egregious differences between the left and the right speakers using peaking equalizers built in MOTU’s DSP.

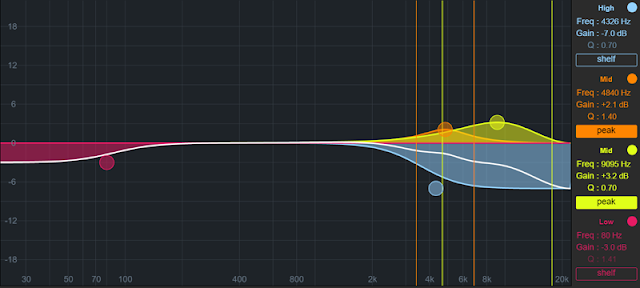

By the way, so far my target was achieving a flat frequency response. The reason is that with such wiggly responses it’s easier to see their alignment while they are jumping up and down around a horizontal line. But this isn’t the desired frequency response for listening, so next I’ve started playing some music and adjusted the “Target Curve” by ear, also using the built-in PEQs of MOTU.

Ideally, I would like to use a “tilting” filter for high frequencies, however MOTU doesn’t offer it. I’ve managed to simulate the tilt using a combination of a shelving filter plus 2 PEQ’s to “pull” it up and start looking like a slope:

I’ve also reduced bass a bit because these KRK monitors use a bass reflex port which produces a bit artificial “booming” bass which tends to mask all other frequencies.

Fine Correction Using Acourate DSP

Having the speakers mostly aligned and adjusted to the desired target curve, there is still a room for some time-domain DSP correction. Let’s look at the IR and the step response of the front speaker again:

As we can see, the drivers on the speaker are not time-aligned: we can see the first small spike from the tweeter, followed by a bigger polarity inversed spike from the woofer, and positive again spike from the bass reflex port. The resulting step response is far from being “tight.” This is something that we can fix using a zero-phase FIR filter produced by Acourate.

One thing that I don’t like about the default filters produced by Acourate is the associated time delay. By default, Acourate produces a filter of 65536 samples, with the peak in the middle. Applying such a filter results in adding a delay of 32768 samples—that’s 680 ms—and this doesn’t account for processing delays. The result is in practice close to 1 second. The author of Acourate—Dr. Brüggemann—was well aware of this problem, so he added an option to produce filters of much shorter length—just 8192 samples, which is enough to achieve most from the corrective effect while keeping the latency relatively low.

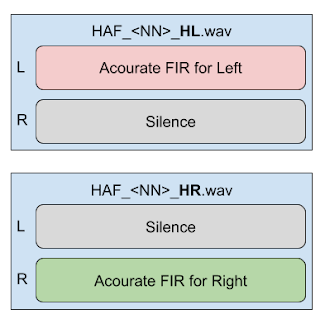

Another technical issue was that since I didn’t have a Windows PC anymore, I had to apply these filters on Mac. AudioVero’s AcourateConvolver doesn’t support Mac directly. I didn’t want trying to run it on a virtual machine either. Instead I’ve ended up using free Audio Units convolver plugin by Home Audio Fidelity. The convolver works with the WAV filters exported from Acourate just fine. I only had to transform mono WAV files with filters into stereo, filling with zeroes the right channel on the filter for the left speaker, and the left channel on the filter for the right channel:

This is because the HAF filters also support crosstalk cancellation, which we don’t use here. The latency resulting from the FIR filters and the plugin is on the order of 250 ms (when using 48 kHz sampling rate), and it actually works fine with videos and video conferences.

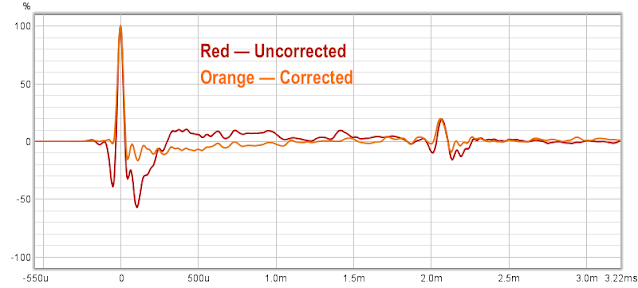

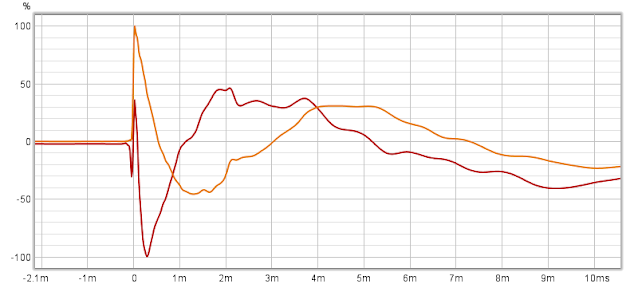

So, what are the results? I’ve took measurements once again on the corrected system. If we look in the time domain, the changes are all for good:

The time difference between the drivers is now gone, and they produce a nice triangular step response, very close to the response of an “ideal” low-pass filter:

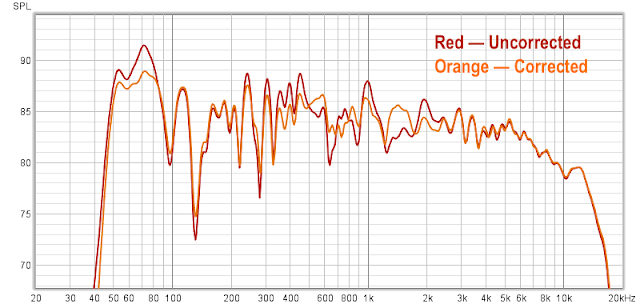

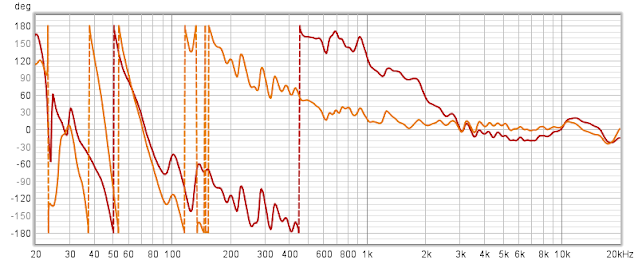

Changes in the frequency domain are less dramatic, that’s because we have already done most of the heavy lifting at the previous stages:

The phase of the speakers actually got more linear starting from 600 Hz:

Note that I only corrected the front speakers. The sub operates at frequencies which are not easy to correct using a FIR filter of reduced length.

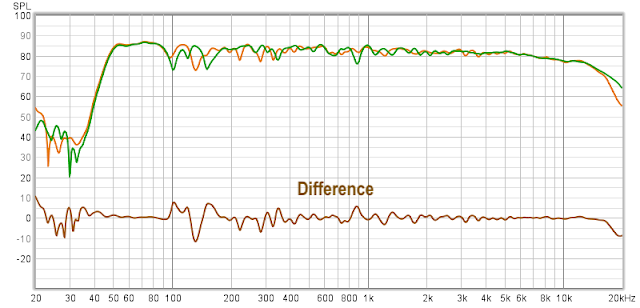

Achieved Left/Right Symmetry

If you recall, my setup isn’t completely symmetrical physically. Nor were entry-level studio monitors accurately matched by KRK. However, as the result of this laborous setup, the amplitude difference between the left and right front speakers is quite low, except for the low frequency range:

Acourate also calculates the Inter-Aural Cross-Correlation coefficient between the impulse responses of the left and the right speaker. It does that for several time windows varying in the duration: 10 ms, 20 ms, 80 ms. The first two results mostly depend on the direct sound from the speakers and the early reflections, the last one depends on reverberation in the room. Since the filters created by Acourate tend to bring both speakers to the same target curve, at least the two first IACC figures are expected to increase with the correction. In my case the improvement was not very substantial:

| IR Time | Before | After | Delta |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0–10 ms | 91.2% | 91.7% | +0.5% |

| 0–20 ms | 80.3% | 80.4% | +0.1% |

| 0–80 ms | 69.0% | 69.8% | +0.8% |

Right, that’s less than 1% improvement. However, numbers don’t always tell the whole story. The time domain correction done by Accurate did improve something in the sound for sure—it has become more “transparent”, reminding me of my LXminis. It has also became easier to subconscuously separate the sound sources in the recording, making the overall reproduction more natural.

The Costs of Corrections

To recap, I’ve aligned my desktop setup in 4 stages:

- geometrical symmetry and acoustic treatment;

- knobs on the speakers;

- IIR filters in the MOTU AVB;

- FIR filters by Acourate, applied in software DSP.

The first two stages add zero latency. Processing done by the sound card adds about 3–6 ms. After these first 3 steps the sound from the system was already good and enjoyable. The last correction added a substantial 250 ms delay, however it did improve the “fineness” of the system. There is definitely the rule of diminishing returns at work.

All steps, except the first one could be corrected by a sophisticated room / speaker correction system (like Acourate) in one set. Was it worth to do them one by one? For me, this makes sense. First, doing full correction with Acourate would require using the default long-tap filters, bringing the latency to uncomfortably high figures. Second, since we know the problems of the system at each stage, we can think of how they can be fixed at the root—usually that’s the most efficient solution.

What’s Next?

So what are the remaining problems and how they can be fixed? This is what I’m considering doing:

- Putting absorbers on the untreated wall and the ceiling to remove the remaining early reflections.

- Getting better front speakers. “Better” here means more point-source like. It could be either LXminis adapted for desktop use, or some coaxial speakers.

- Adding a second subwoofer to make the right speaker full-range, and thus achieving symmetry with the left one.

- Reducing the latency associated with the FIR correction by employing some hardware DSP.

Another interesting option for making this setup more “immersive” is to try to reduce cross-talk between the speakers. This again will require some serious DSP processing.