Mikhail Naganov

Understanding Git, Part 2

Publishing the next part of my talk about Git. See the first part here.

Let’s continue to the second part of the talk. Whereas the building blocks we were considering in the first part are more or less abstract and can be used for understanding generic principles of any distributed version control system, the areas and especially commands are specific to Git.

Let’s start with Working tree and Index. The Working tree is something that is understood by all Git users—it’s their sandbox where they do all your edits and file structure manipulations. It can be also referred to as “Working Directory”.

As for the Index, it’s a more confusing area and depending on your experience with other version control systems, index can be either a benefit or a hazard (rephrasing Rick Dekkard). Some version control systems do not have index, thus changes in the working tree are immediately committed into the repository. Not so with Git. Here, Index is an intermediate area where the next commit is staged. That’s why Index is also referred to as “Staging Area”. In order to commit a change to the file, it must be first registered with Index.

Because Index sits between the working tree and the repository, it is also referred to as “Cache”. No wonder why reading Git’s messages and help pages related to Index can be very confusing! Speaking of the building blocks we were considering earlier, both Working tree and Index can be represented as Tree objects. Also note that both Working tree and Index are optional and are only needed to prepare new commits. On a headless Git server they do not exist as there are no users who would commit changes to the server repository directly.

As an example, let’s consider typical output from the git

status command. The above output

appears when there are changes both to the index and to the working

tree. The changes that have already been registered with Index are

listed first. Changes that haven’t yet been registered are listed at the

bottom.

Note that the same file can be listed in both sections meaning that some of the changes in it are in the Index and some are not. That illustrates the “benefit or a hazard” behavior. On one hand, index allows you to split the changes your are making to the working tree into several commits. But this also can produce an unfinished commit that misses some changes you’ve done in the working tree but forgot to stage.

In this output Git hints us about some commands that can be used in order to move files between the index and the working directory. Let’s explore them.

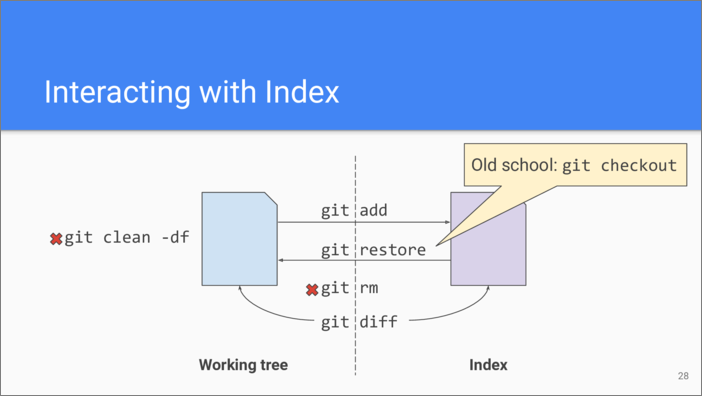

git add is used to stage to the

index any changes in the file. It’s also used to put a file under

version control. If you want to undo the changes done to the file in the

working tree and use previously staged version, use git

restore command. This is a

relatively new command and long time git users know that a more

universal git checkout

command can also be used for the same purpose.

If we want to remove the file from under version control, we use git

rm command which erases it in the

working tree and also removes from the index. If there are any untracked

garbage files or directories in the working tree, they can be easily

removed using git clean

command.

If we want to see the changes done to the files in the working tree

compared to the staging area, we need to use git

diff command which generates a

diff object.

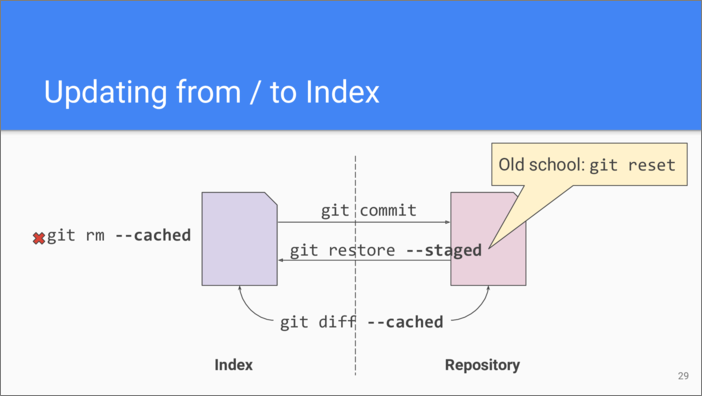

Moving onto the next level, let’s consider how do we move changes

between the index and the repository. The git

commit command is well known—it

creates a commit object that points to the tree object of the index and

adds both to the repository.

In order to see the changes before we commit them we can use git

diff with --cached argument—it shows the difference between the

index tree and the tree from the last commit.

Previously mentioned git rm and git restore commands can be used

to remove or undo changes in the index. Note that there is an

inconsistency between the argument names they use.

And of course, there is no direct way to remove a committed change from the repository.

An interesting question: what does it contain in a “clean” state, e.g.

after doing git checkout or git

reset? A good answer to this

question is in the “Reset demystified” section of “Pro Git”

book.

On checkout, the tree of the index is the same as the tree from the

checked out commit (and same as your working dir assuming you haven’t

made any changes to it yet). Thus, both git diff and git diff

--cached produce an empty diff immediately after a checkout. If we

make a change in the working directory to an already tracked file, git

diff shows it. Once we stage this change (git add), it is now

shown by git diff --cached, but isn’t shown by git diff.

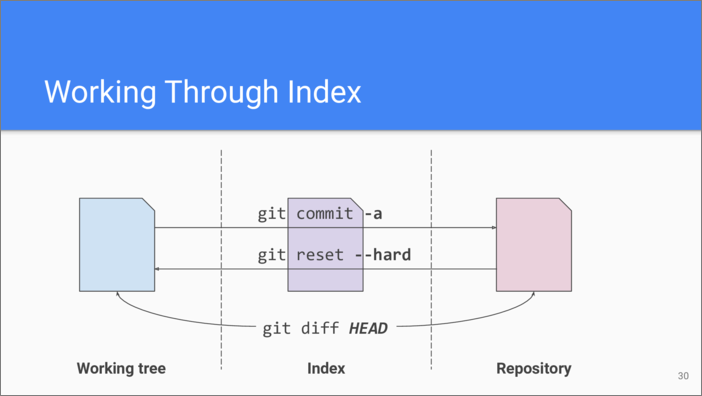

Finally, for those users who don’t want to fiddle with the cache, there

is a way to work through it, as if it didn’t exist. Using -a

argument with git commit command automatically puts all the current

changes from the working tree into the index before creating a commit.

git reset with --hard argument can be used to replace the

contents of the working tree and the index from the last commit in the

repository directly. And git diff HEAD (all caps) can be used to

show combined differences between the working tree plus index and the

last commit. git diff HEAD puts the tree of the working dir on top

of the tree of Index and diffs the result against the tree of the last

commit (so if there are both staged and unstaged changes to the same

line the latter will be shown).

What is HEAD, exactly? It’s a special reference in the repository that we consider next.

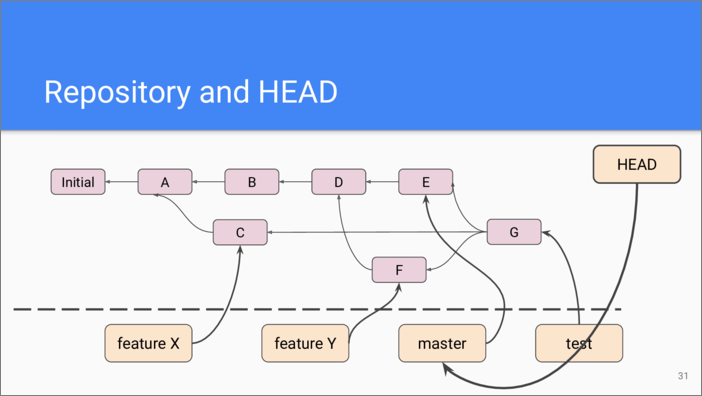

This is the already familiar diagram of the commit graph with branches. HEAD usually points to what is called “current” branch—the line of changes we are working on. Note that HEAD is a meta-reference—instead of pointing to a commit via its hash it instead contains the branch name, thus when we use HEAD, double dereferencing is needed to get to the commit.

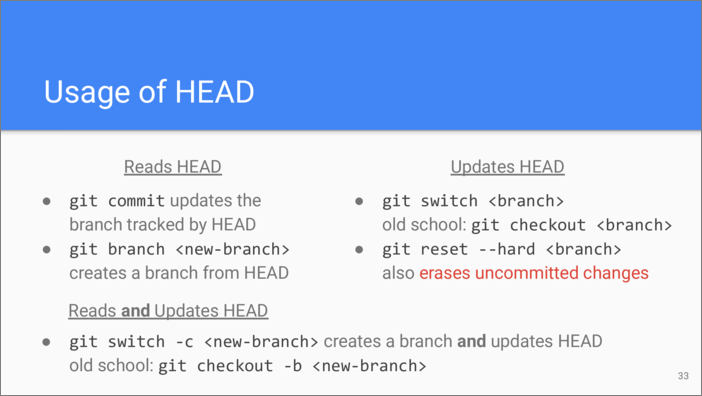

This is how HEAD can be used and changed. When we do a commit, git

commit uses HEAD to get to the last commit on the current branch and

make it the parent of the freshly created commit. Then git commit

updates that branch to point to the new commit.

git branch command can be

used for creating a new branch without switching to it. A relatively new

command for changing the current branch, and thus updating HEAD is

git switch. Note that git

switch will refuse to work if there are any uncommitted changes in the

working tree, because switching to a branch also means populating the

working tree contents using the last commit of the branch, and any

uncommitted changes will be lost. In case we actually want to lose them,

we can use git reset --hard and provide it with the branch name.

git switch with -c argument is used for creating a new branch

and switching to it (that is, updating HEAD).

People often ask, what are the differences between relatively new git

restore and git switch commands vs. good old git checkout and

git reset. There is an excellent write-up on GitHub

blog about

this. In short, git restore and git switch are safer

alternatives to old commands, but they don’t replace them fully. There

are some similarities in their arguments, e.g. for interactive

piece-by-piece restoration both git reset and git restore use

-p argument, but there are differences too, e.g. git switch -c

is the same as git checkout -b. In general, the arguments of the new

commands should be more straightforward and easier to understand.

The old multi-purpose git checkout command can be used for changing

HEAD, too. Unlike git switch which only accept branch names, git

checkout can switch HEAD to any commit.

However, if the commit is not referenced by any branch, switching to it

creates a so called “detached” HEAD. This isn’t a normal state for

development as git commit will not be able to refer the new commit

from any branch. That means, the new commit will be considered “garbage”

by Git and removed from the repository sooner or later.

That’s why Git displays this lengthy message when you switch to a

detached HEAD. BTW, it also hints you about a quick way to flip between

the last two branches by passing minus (-) argument to git

switch. The takeaway is—if you see this message, don’t commit any

changes unless you really know what you are doing.

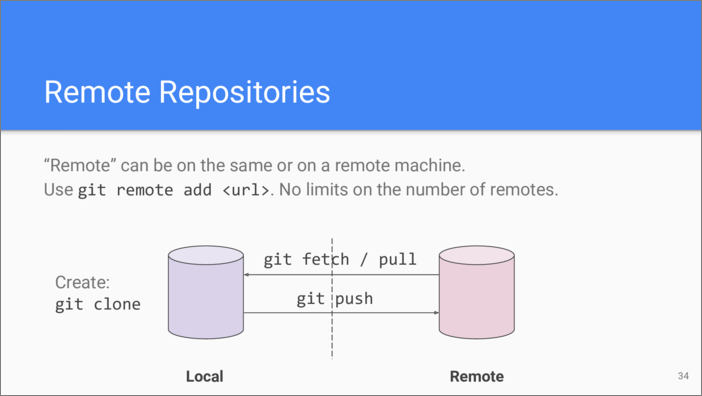

As Git was created for distributed development, it natively supports synchronization with remote repositories. “Remote” doesn’t necessarily means that data is on another machine, it can reside in a different folder on the same hard drive.

To add a remote, use git remote add

command. As you can guess, Git sets no artificial restrictions on

how many remote repositories you may have.

Let’s do a brief recap on the main commands dealing with remote

repositories. git clone allows

starting a new local repository from a remote one. It’s a shorthand for

creating an empty repository, adding a remote and syncing from it. There

are actually two commands for syncing: git

fetch and git

pull, we will consider the

differences between them later. git

push is used to sync your local

changes back to the remote.

You never manipulate the contents of remote repositories directly. When you sync from a remote repository, all its objects and references get imported into your local repository, thus it effectively becomes a cache for remote data. After you’ve made any changes which means you have created new objects and changed references, these changes can be synced back to the remote using the same synchronization process.

As Git was designed as a peer-to-peer system, it doesn’t matter which side initiates data transfer. The remote side can request data from you, or you can push your local data to remote side. In the latter case you must have the necessary permissions.

Now let’s talk about the difference between git fetch and git

pull. The former doesn’t change the state of your branches or the

working tree, it just does the synchronization. git pull by default

is a shorthand for doing git fetch and then executing git

merge. UPDATE: You can pass

--rebase argument to do a rebase instead.

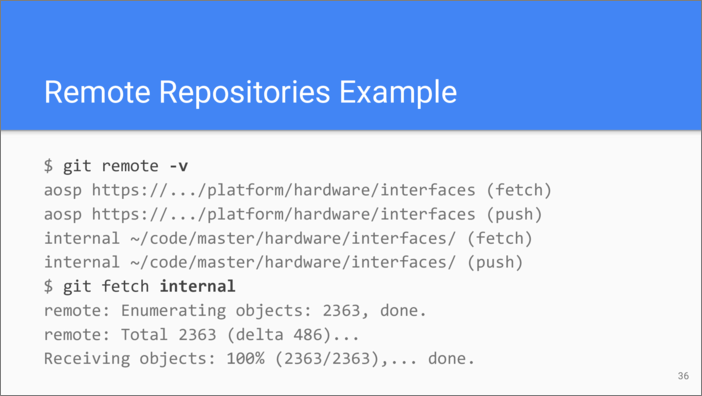

Here is an example of using git remote command. First, we list the

remotes by passing the -v argument. There are two remotes here, one

called “aosp” which is accessed via HTTPS, and another called “internal”

which lives on the same machine. It’s possible to use different URLs for

fetching and pushing.

Then we execute git fetch command to receive any new objects and

references from the remote called “internal”. After it has finished you

can access the contents of objects received from the remote.

As we know, branches are the entry points to repository objects.

Obviously, it’s a good idea to use branches of the remote repository to

access its commits. From the building blocks point of view they don’t

represent anything new—they are also files pointing to commits. However,

because conceptually they are in remote repository, they can’t be

updated in any other way than syncing from a remote. For the same

reason, if you attempt to do a git checkout using a remote branch

name, this will result in a detached HEAD.

The name of a remote branch reference is the same as the name of the branch in the corresponding remote repository. For namespacing purposes, names of remote branch references are prefixed with the name of the remote.

And here is another term from Git vocabulary—a ”tracking” branch. Since remote branch references are read-only, in order to do any development on a branch coming from a remote repository—it is called “upstream” branch—you need to have a local branch. Usually it has the same name as the upstream branch, but that’s not mandatory. The name of the upstream branch is stored in the metadata of the “tracking” branch.

If you attempt to switch to a non-existing branch using the same name as

one of remote branches has, Git will automatically assume that you want

to create a new branch that should track that remote branch. In order to

have control over this behavior, you can use --track argument of the

git switch command.

Here is an example of what happens when you switch to a local tracking

branch after doing git fetch. If there were remote changes on the

upstream branch since the last sync—the last common commit is labelled

“C” on the diagram—Git will offer to merge your local branch with

the remote branch to integrate the changes together. Since these

branches have diverged, a fast forward is not possible, and a merge

commit will need to be created.

If you are not allowed to have merge commits, then instead of doing a merge you should rebase your changes on top of remote changes. We will consider the mechanics of this a bit later.

Enough with remotes, let’s talk about the tool that helps handling work interruptions. Sometimes you are in the middle of working on a change and then something unexpected happens: your previous change has caused a build break and a simple fix is needed immediately, or you’ve got some ideas and need to test them quickly on some other branch. You don’t want to lose your current changes, but you also don’t want to commit them as is.

One possible way of handling this is to create a branch and commit your

current changes there, then checkout another branch to restore the

working tree contents to a known state. However, there is another more

convenient solution—to stash the change away using git

stash command. This command saves

your current index and working tree modifications into the repository as

commits and brings the working tree and index into the previous

committed state.

In terms of building blocks, Stash is just another reference, like a branch. However, the last stashed commit does not use the hash of the previously stashed commit as a parent. It’s actually interesting to understand how stashing is implemented.

Let’s say we have the last commit called “M”. We have made some changes

and added them to the staging area, then we have also made some changes

to the working tree and haven’t yet staged them. Now we execute git

stash, what happens?

First, Git creates a commit from the contents of the index, setting “M”

as a parent—as if we have executed git commit command. This commit

is shown as “I” on the diagram. Git also snapshots working tree contents

and creates another commit for them, called “W” on the diagram. This

commit has two parents: “M” and “I”, so this is a merge commit. The

stash reference is then set to point to that commit. After that, Git

resets the index and the working tree to the state of the commit “M”.

This brings up a question: if we do git stash multiple times, how

can we find previously stashed commits?

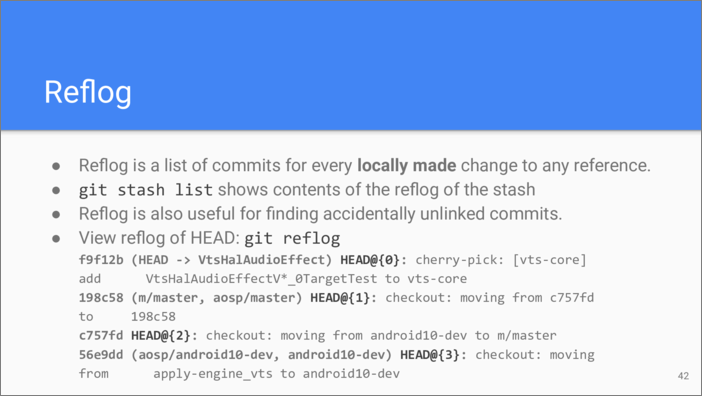

To answer the question, we introduce another powerful tool of Git—the Reflog. Speaking in terms of building blocks, this is just a list of commit hashes. The power comes from the fact that Git adds a node to this list every time any local reference changes. This includes HEAD, branch references, and Stash.

So, answering the question we have previously stated—in order to find

previously stashed commits we can look into the reflog of Stash. git

stash list command does exactly that.

Another useful application for reflog is finding commits that you have

accidentally unlinked from branches. You can find their hashes either in

the scroll buffer of your terminal—if they are still there— or in the

reflog.

Here is an example of executing git

reflog command. It lists the

history of changes to HEAD. The reference specifications in the reflog

commits list use special syntax which we will consider later.