Mikhail Naganov

Understanding Git, Part 3

The final part of my talk about Git. Here are Part 1 and Part 2.

After familiarizing ourselves with the areas of Git repository and basic commands, let’s dive into practical application of this knowledge. In this last part of the talk we will consider how to manipulate changes to achieve your goals, how to track what other people have done, and how to get out of trouble.

Let’s start with understanding how to make amendments to changes. This is useful to correct any mistakes you’ve discovered after commits have already been submitted into local repository. Also, amending your previous changes is required if you are working with a distributed code review system like Gerrit.

As you can remember, the actual commit objects residing in the repository are immutable and can’t be changed once you have created them. However, what we can do is come up with another set of commits, trees, and blobs, connect the new commits to the commit graph, and update the branch reference to point to the new set of commits.

This is illustrated on this diagram. Imagine we have a master branch which points to commit D. We have realized that we need to amend the last two commits: C and D. We use them as starting points for creating new commits, beginning from the oldest one—C. When we create this new commit we can optionally use a different parent commit for it.

After we have created the last new commit—D’ in this case, we reset the master branch reference to point to it. Now although the old commits C and D are still in the repository, Git will consider them garbage at some point as they are not referenced by any branch.

Note that even if we didn’t change the trees of C’ and D’ compared to the original commits, but just reparented C, it will still be a different commit because the commit hash is calculated from entire commit contents which includes the parent reference. And since C’ becomes a different commit with a different hash, D’ is also different from D even if it still references the same tree.

That was a generic case of history rewriting, let’s consider the

simplest one—amending just the last commit. Git has a special option for

the git commit command, which is called --amend. If you haven’t

staged any changes, executing this command will only result in updating

the commit message of the last commit. If you have staged any files,

they will replace corresponding files in the last commit.

As always, you can skip the intermediate step of staging by passing the

-a option together with --amend.

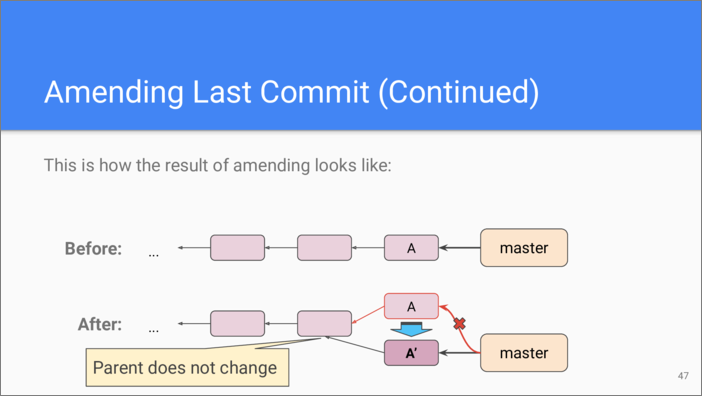

And this is an illustration of what happens when you amend the last change. The tree of the commit may change or it may stay the same. The commit itself changes if you change the commit description. The parent of the amended commits stays the same. Your current branch gets updated to point to the new commit object.

Let’s consider a more interesting example of amending commits. Imagine we were developing two features: X and Y in dedicated branches, and now want to integrate them into a single branch.

As we mentioned earlier, one way of doing that is to create a merge commit. If that is not an option, then we can take the changes specific to one of the branches and replant them onto another branch.

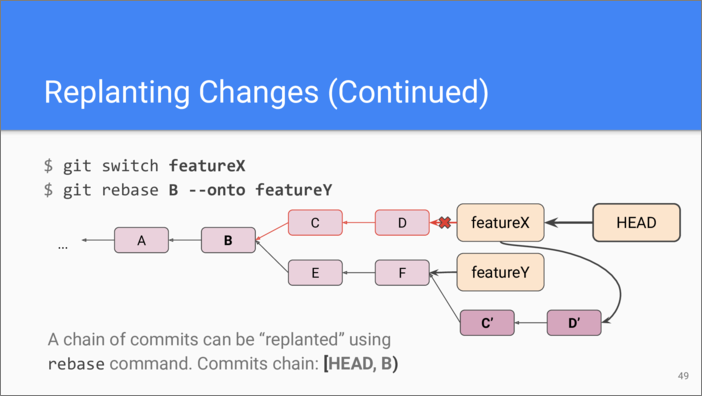

This is how we do that using git

rebase command. Imagine we

decided to take the changes from the featureX branch and rebase them

onto the featureY branch. For that, we make the featureX branch

current, then we provide git rebase with the identifier of the

change that ends the commit chain, in this case this is commit B,

and the destination branch: featureY.

What happens next is Git takes the commits from that chain and, one by one, plants them onto the destination branch. Then it updates the branch reference. Note that the current branch remain the same after rebasing, thus the HEAD meta-reference doesn’t change.

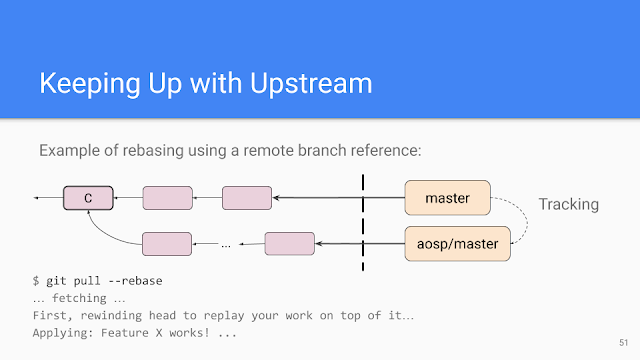

Here is another practical example of rebasing, this time using a

tracking branch. This scenario happens when you are working on a branch

which is being changed in a remote repository by someone else. Recall

that by default when you do a git pull Git merges your local changes

with remote changes. Instead we can do a rebase by specifying

--rebase argument. In this case git will automagically rebase your

local changes on top of remote changes. Here is how this happens.

To demonstrate what happens, let’s do the same that git pull

--rebase does, but this time manually.

First we sync with a remote repository using git fetch. By comparing

positions of the tracking and upstream branches, Git can find out that

there are 100 new changes happened upstream, and we have a couple of

changes, too. This is in fact the same situation as we have considered

earlier with two features. The only difference is that this time one of

the branches is a remote branch reference.

Now we do a rebase. We don’t have to specify the fork point and the

destination branch to git rebase this time, because Git assumes we

are rebasing onto the upstream branch, and it can figure out the fork

point itself. After rebasing we have our changes on top of the changes

from the upstream, as expected.

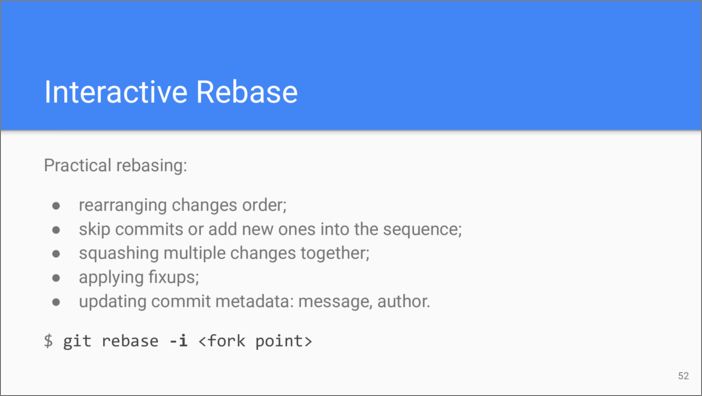

Since while we are rebasing we are creating new commits, it’s possible to apply more radical changes rather than just changing a parent or amending files. With Git interactive rebase we can also re-apply changes in different order, skip some changes, or add new ones, and combine multiple changes together. Basically, if you recall our “Patch algebra”, we can do all those operations on actual commits.

For that we use -i (for “interactive”) option to git rebase.

This power of being able to rearrange our changes in the hindsight allows us to apply “working in small steps” philosophy. What this means in practice is that we commit our changes as often as possible. Usually it’s after we have completed some logical step and the code at least compiles, although this is not a requirement. This allows us to rearrange our changes later, or to find a change that has broke everything.

Even if we use a code review system for the project, working in small steps is beneficial because by the time when we are ready to get our changes reviewed, we can group them into bigger chunks.

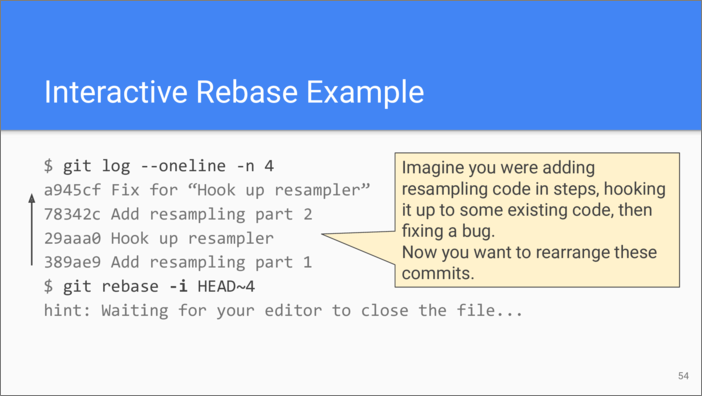

Imagine we were working on adding a resampler to our audio code. Let’s say, we have implemented the resampler partially, then hooked it up to existing code, then finished implementation, and then have fixed a bug in the integration code.

Now what we can do is fire up an interactive rebase to organize those changes into a more logical form.

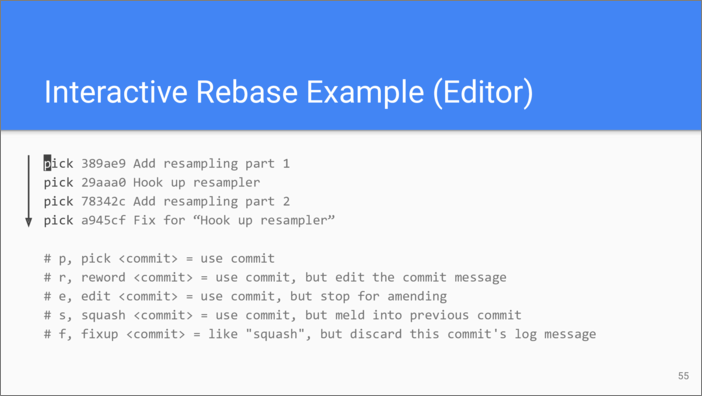

After we have run git rebase -i we end up in our favorite text

editor. Here we are presented with a list of changes. By default, Git

will just pick them one by one, and this will result in no new

commits, because no data will change. However, the interactive rebase

offers a wide choice of operations listed below.

It is important to note that the commits are listed in direct

chronological order (oldest go first), which is opposite to the order

normally used by git log.

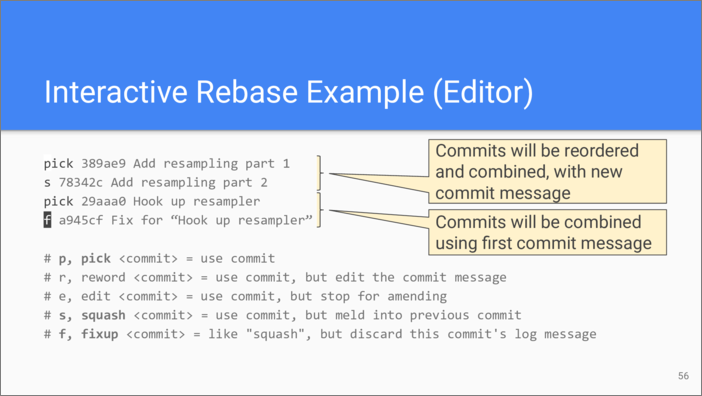

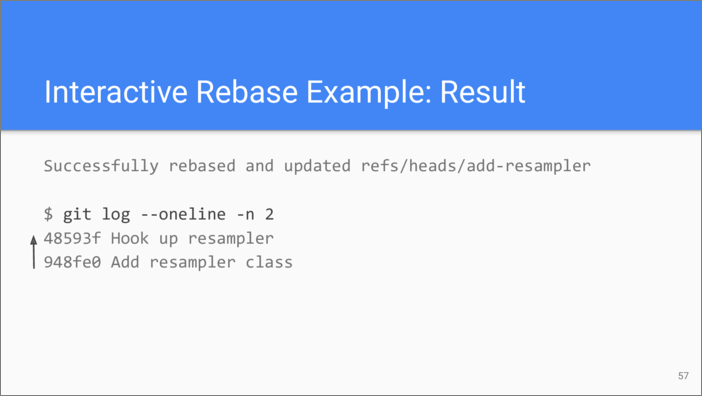

So what we have done here is we rearranged the changes in order to group

together the two changes that implement the resampler. We use the

squash (“s”) command to combine these changes and to edit the

message of the resulting commit. On top of them we put the plumbing

change and the fix for it. For the fix, we use fixup (“f”) command

which simply uses the commit message from the first commit.

After we have done with editing the interactive rebase instructions, Git follow them, and this results in a new sequence of commits.

There is also a manual alternative to rebasing, known as “cherry-picking”. We can basically replant changes manually one by one in the order we want. This can be used, for example, if you want to try a new approach in a new branch, but want to reuse some of the work you have done on another branch.

What you do is you use git

cherry-pick command

providing a list of commit identifiers as parameters. There is no option

to squash commits.

In this example, we decided to try to hook up our resampler in a different way, so we start another branch using master branch as a starting point, then we find out the hashes of the commits we are interested in, and apply them in the right order to our new branch. Obviously, this will result in new commits being created.

In the examples above we used a couple of times special syntax to reference commits that are ancestors of HEAD. The time has come to understand it. I called this section “Mini-Languages” to refer to the concept of Domain-Specific Languages. I also introduce Git-specific jargon here that is encountered in the documentation.

Let’s start with what is called “refname”, which I guess means “the name of a reference”. If you recall, HEAD is the name of the metarefence to the current branch.

Obviously, the name of the branch is a refname too, because as we know,

any branch is a reference. If a local branch tracks a remote branch, we

can retrieve it using @{upstream} syntax.

Another Git jargon word is “rev” which is a short name for “revision”, and that means specifying a commit. The canonical way is to use the full SHA-1 hash of the commit. However, it’s usually enough to specify just a few first characters of the hash. For small repositories, something like 5 first characters is enough, and for big ones we might need to provide up to 12.

Since the contents of a branch reference is a commit hash, a branch name

can be trivially resolved into a commit. That’s why any Git command

requiring commit hash will also accept a branch name.

If we have a rev, which as we remember is equivalent to having a commit,

we can reference the Nth parent of this commit by using the ^N

syntax. If N isn’t specified, it’s assumed to be 1.

Since the parent of a rev is also a rev, we can apply the ^

“operator” multiple times moving one parent away with each application.

There is a short syntax for this—~. If N isn’t specified

it’s assumed to be 1, thus a ~ alone is equivalent to ^.

And finally, this is the syntax we’ve seen when we were talking about

reflogs. Recall that a reflog is the list of changes happened to a

reference. In order to reference the Nth previous state, we use

@{N} syntax.

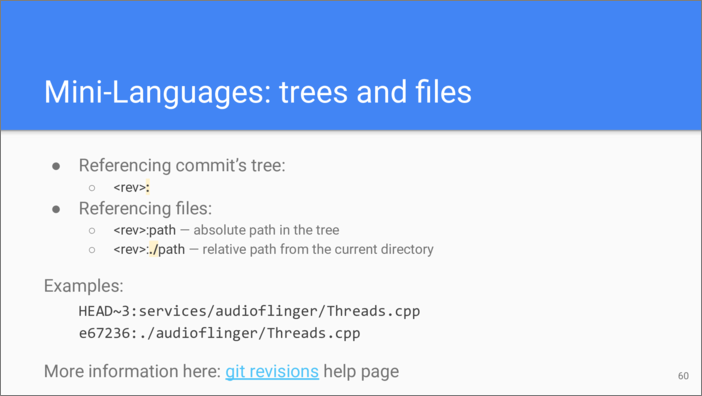

As you remember, every commit has a tree object associated with it. You

can reach that object by adding a colon (:) after the rev. And once

you’ve got a tree, you can go down by it and reference files it

contains. This way you can designate the state of any file at any

commit—kind of a time machine.

Since you typically execute Git commands from some subdirectory of your

working tree, Git can use the current path for resolving a relative

path. The relative path is specified by prefixing it with ./

character sequence.

Here are a couple of examples. Both assume we are working with the

frameworks/av repository of

Android. The

first example references the state of the file

services/audioflinger/Threads.cpp 3 commits ago. The second

example assumes that we are currently in the services subdirectory

of that repository, and references the state of the same file at the

specific commit.

Consult the git revisions help page for the full list of options.

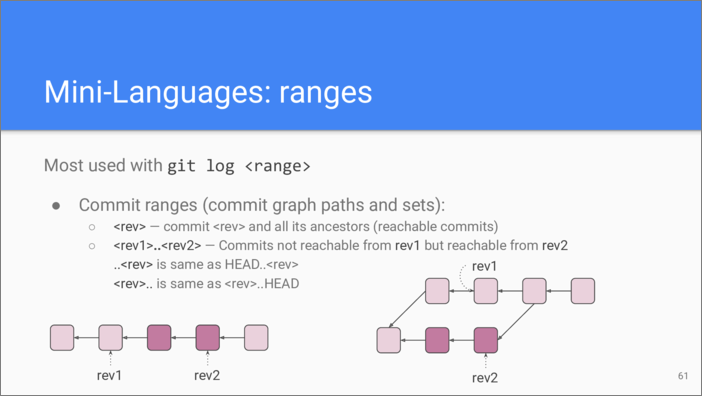

So far, we were talking about how to reference just one commit. It is

also useful to be able to specify a section of a path in the commit

graph. This is called a “commit range”. A commit range may also denote a

set of commits which are disjoint in the commit graph. Commit ranges are

frequently used with git log

command.

If you provide git log with just one rev, it will interpret it as

“all the paths that go down from the commit <rev> to the initial

commit”. Actually, if you don’t provide any revision specification to

git log it will simply take HEAD. The problem with that is the fact that

the path from HEAD to the initial commit is quite long. In order to

restrict the range we can use .. syntax, as shown here:

<rev1>..<rev2>. This means “all commits not reachable from

rev1 but reachable from rev2 (including rev2 itself)”.

In case of a linear history (when no merge commits present), this is simply the path from the commit rev2 down to but not including rev1. However, with non-linear history the result can be more interesting, as we can see on the diagram on the right.

In you don’t specify rev1 or rev2 in the range, Git will use HEAD.

Similar to printf function in

C, Git has a

template-based mini-language for specifying how to format the output of

git log and other commands that can display commits, like git

show. There is a set of predefined

formats, called “pretty” in Git jargon. You can also construct a format

that suits your needs by using placeholders prefixed with the percent

symbol %. I’m not listing them here because usage of this

mini-language is pretty straightforward and you can look up all the

formatting instructions on the git

pretty-formats help page.

Now we are armed with the knowledge of how to specify objects we want to view and how to represent the results. Let’s consider the commands that can be used for viewing different kinds of objects in Git.

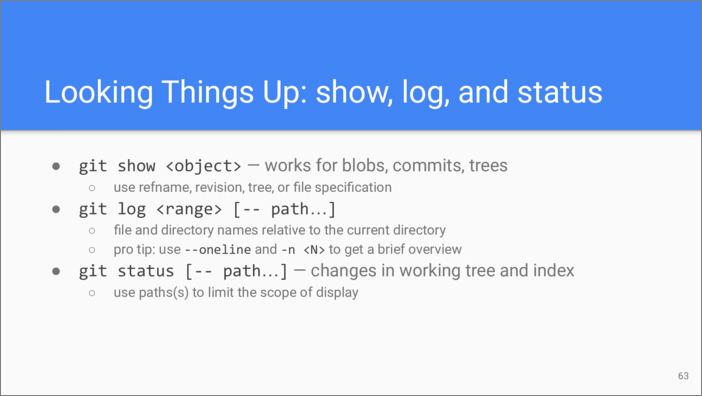

A versatile command git show can display any repository object: a

blob, a tree, or a commit. You can provide either the hash of the

object, or a rev, or a path specification we have considered earlier.

The next command is well-known git log. It accepts a commit range,

and its output can be limited to only consider certain paths so you can

view changes specific only to a certain file or a directory. Don’t

forget that you can specify output format and number of commit entries

to display to make the output more manageable.

And finally, git status command which we have seen before. Its

output can also be scoped to a certain path.

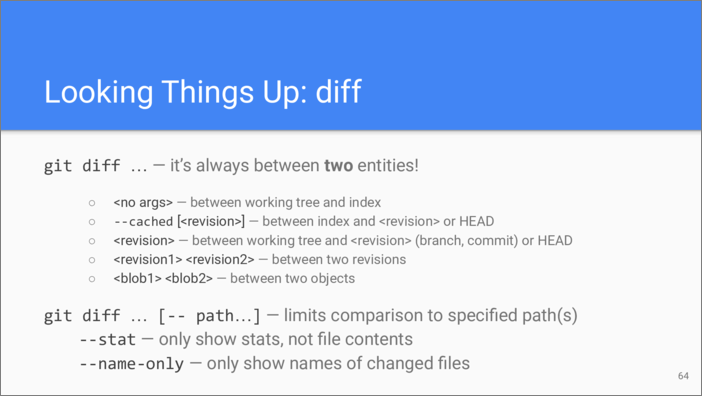

As we have discussed before, Git doesn’t store any diffs in the

repository but generates them on request, for example when you invoke

git diff command. Remember that diff is always generated from two

objects, even if you specify only one or even no arguments to git

diff. Here on the slide I listed possible useful options.

Sometimes we are not interested in seeing an entire diff. What we can do then—first, limit diff output to a certain path or paths. We can also ask diff to only display what is called in Git the “diff stats”—the amount of lines changed in every file. We can even only display the names of the changed files, with no extra information.

Of course you know about git

blame command in Git. It’s

perfect when you can immediately find the commit that made the change in

question to the file. However, it’s not always that easy because in big

and long-living repositories a lot of refactorings happen that just move

lines between files or change formatting. But there is always a way to

find the first functional change.

In this example, let’s consider this fragment of code from Android’s

frameworks/av

repository.

Let’s say we want to find out the reason why “FLUSHED” state of a track

is also considered as “stopped” state. From git blame output we can

see that this line was last touched by someone named Eric in the commit

with the hash starting from 81784.

We use git log to check the description of this commit (we could

also use git show to view the entire commit), and unfortunately this

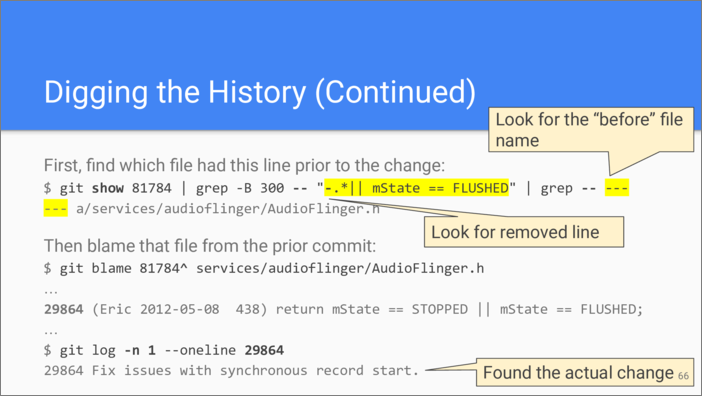

last change was just code reorganization, so we need to look deeper.

It’s a bit of a problem that the line has been moved from one file to

another. We need to find which file had this line before. One way to do

that is to go manually through the change, and that’s doable if the

change is small. In this case, the change was quite big so I used

grep in order to find this line in the output of git show. I

instruct grep to show a lot of lines (300) before the match to

see the name of the original file and then grep the output once more

just to show the line with the file name which diff prefixes with three

dashes (---), as we can recall from our discussion of the patch

format.

So I can see that the line was originally in AudioFlinger.h file.

Now I instruct git blame to start looking from the ancestor of the

refactoring commit. I use the hat (^) here to specify that

revision, I could also use a tilde (~) if you recall the slide

about revision specification. And I specify the name of the file I want

to blame.

Now I see the last commit that actually changed this code, it was also made by Eric, and from looking at the description and probably diff, which didn’t fit on the slide so it’s not shown, I can see that I finally have found a functional change.

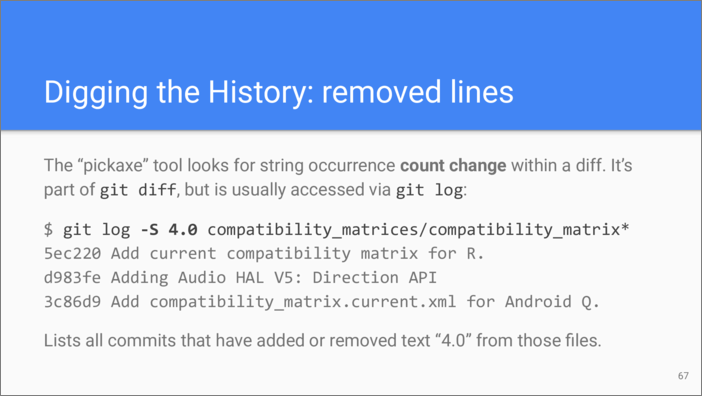

So git blame is really useful for figuring out commits that have

changed a line of code. But changes can also remove lines of code.

Obviously, we will not see the removed lines in the output of git

blame. In order to see the history of removed lines, we can use the

“pickaxe” tool of Git.

Recall that in diffs, each modification of a line of text is described as the removal of the old line of text, and the addition of the new version of that line. Any line can also be removed in one place of one file and added to some other place, maybe in some other file. Obviously, if the change adds a new line, there will be no old version of it. If the change removes a line, there will be no new version.

So what “pickaxe” does—it counts the amount of diff lines that remove a

line containing a specified string, and the amount of diff lines that

add it back. If these numbers do not match, that means the line has been

added or removed in this diff. And this is what pickaxe reports.

In this example we are looking for changes that add or remove string

4.0 from the set of files. We provide -S argument to git log

which invokes the pickaxe tool.

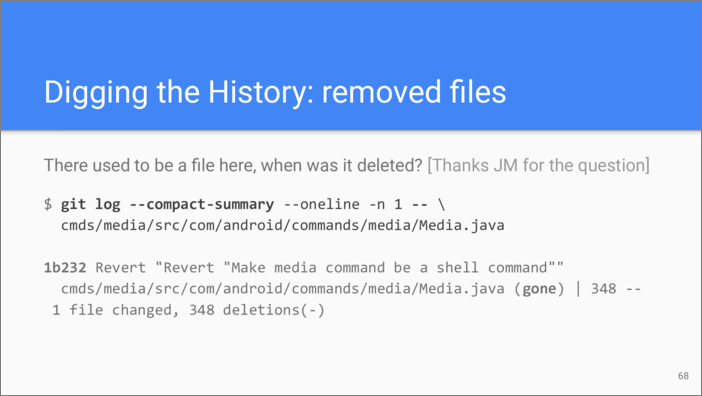

Some commits add or remove not just lines but entire files. Once our

colleague Jean-Michel couldn’t anymore find a file that he knew existed

before. He wanted to find the change that removed that file. That’s

actually easy with git log which supports --compact-summary

argument which only displays “diff stats”. We limit the scope of git

log to that particular file and here is what we see—the last commit

that had removed the file.

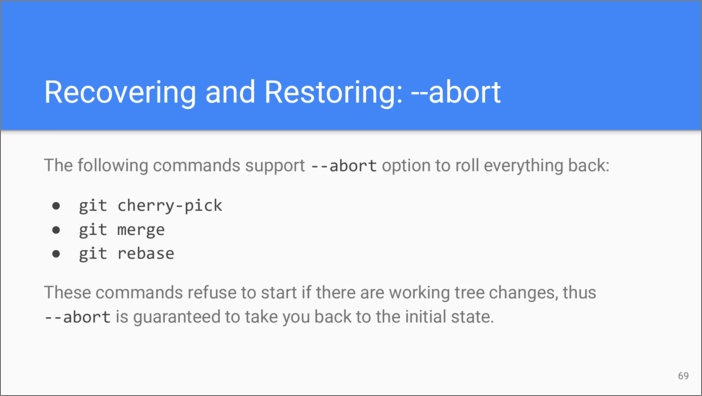

Managing commits is a complex business and sometimes things do not go as

you expect. Remember that Git always allows you to pull out from a

multi-step operation like rebasing or merging and get back to a clean

slate. To pull out, just re-run the same command with --abort

argument. Because all of the listed commands check before starting that

there are no changes to the working tree, they guarantee that after

aborting you end up in the state you were initially.

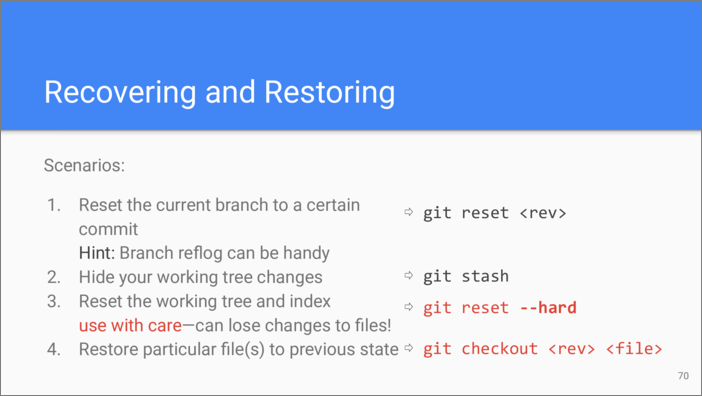

Here are some more Git commands that can help getting your working tree

and index back to some good known state. First, there is git reset

command which, if called with only a revision parameter resets the

branch reference to the specified revision. You can always look up any

previous state of any branch by examining its reflog, as we discussed

earlier.

Second, recall about the git stash command which you can use to

clear out of your way any uncommited changes without losing them. If you

are sure you want to lose them, use git reset --hard command.

And finally, you can always restore any particular file to a previous

state using git checkout command. Recall that Git repository is a

time machine that stores the state of any file at any previously

committed revision.

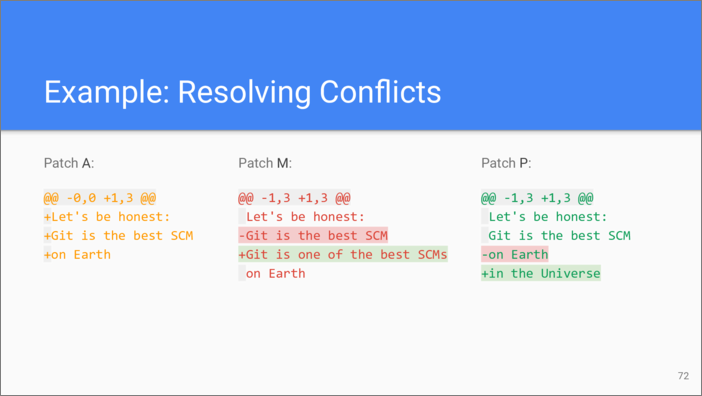

There is one thing in version control management that people hate as much as going to the dentist or paying taxes—it’s resolving merge conflicts. Let’s try to understand this problem better using the “patch algebra” we have discussed in the first part of this talk. In terms of patches, on one branch we have a file in state A to which a change M had been applied. Then on another branch the same file has received a change P. Now we are trying to merge these changes together. Recall that any change in the diff has a context. A merge conflict occurs if the change M modifies parts of the file that are included in the context of the change P.

A lot of times Git can work around these discrepancies and still apply the patch. However, sometimes the help of a human is required. What I highly recommend to do is to configure Git to use so called “diff3 conflict resolution style” using the command shown on the slide because it provides the most comprehensive information about the conflict.

Let’s consider an example. The change A which is common to both branches adds a file with 3 lines of text. Now let’s imagine that two persons have made two different changes to this file. The change M was done by a humble developer, while the change P was done by a more optimistic marketing person.

This is how Git presents this conflict to you using diff3 style. First goes the part of the file that hasn’t been changed. Then the change on our branch (change M). Then how was this part looking prior to the change on the remote branch, that is, the parent of the change P. In our case this is actually the same as the state A. And finally, how this part looks with the change P applied.

Now what we need to do is to either select one of the versions, or produce a new version which for example combines both changes. We also need to remove the lines with merge conflict markers. And we repeat this process for every conflicting hunk.

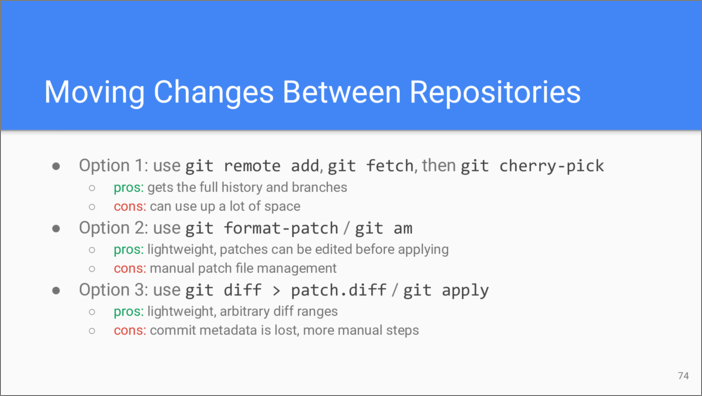

Another common scenario we encounter when working on Android is the need to transfer a change from one repository to another. Here Git offers several options.

The first one is to add the second repository as a remote, fetch its contents into our repository, and then cherry-pick the commit containing the change. The problem we encounter here is that with large repositories fetching objects from another repository will take a lot of time and end up consuming a lot of disk space.

So if we are not interested in the history of the change we are

transferring, another option is to use so called “mail exchange”

scenario. We use git

format-patch command on

the source repository to export the change in the form of a diff file

that contains all the commit metadata, and then apply this diff to the

target repository using git am

command. git format-patch produces a series of files, one per

commit, so we can end up with lots of files.

Finally, instead of using git format-patch, we can produce a diff

using git diff that contains all the changes we are interested in,

possibly from multiple commits, and then apply it using git

apply command. But since in this

case the diff will not contain commit metadata, we will need to provide

it manually.

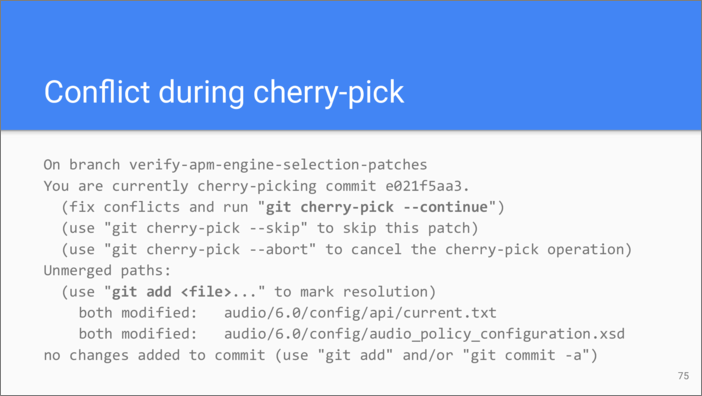

Note that while transferring changes from one repository to another it’s a common situation to encounter a merge conflict, because repositories are likely diverged significantly one from another, like Android internal master and AOSP. If there is a conflict you will be presented with the following instruction from Git.

What you need to do is to go over the files that have conflicts, resolve

them, and then stage updated files using git add. Then you can let

Git to continue.

As I’ve mentioned before, if anything goes wrong, cherry-picking can be aborted at any moment.

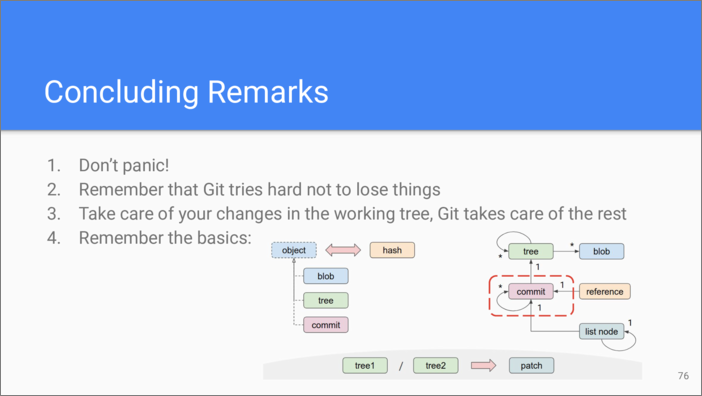

These are the final tips for your Git journeys. First, don’t panic! Remember that Git is a time machine and there is always a way out. Second, remember that with the way Git repository is organized it’s actually hard to lose anything. Most probably, your changes are somewhere in the repository, you just need to find them using one of the tools we have discussed. Third, the most important thing you must care about is files in your working directory—if you haven’t saved changes to them and you overwrite your working tree, that’s it—they are lost forever. So take care of the changes you are doing in your working tree and let Git takes care about the rest.

And finally, if you are losing track of what’s going on, recall the building blocks diagram. Commit objects are the keys to everything, so if you need to find something, always start with finding the corresponding commit.

And there is always more to learn about Git! Here are several recommended sources. First, it’s the free book about Git called “Pro Git”.

If you are a visual thinker like myself, then “A visual Git reference” provides a lot of illustrations on what Git commands are doing to Git objects.

Finally, I’m pretty confident that if you’ve got through this talk you

are now able to understand the text of official Git documentation pages

:) Invoking git help command

with the name of another command as a parameter provides you with pages

of text you might now even find helpful.